REDEFINING LUXURY

By Sarah-Linda Forrer

In our "9 Questions" interview series, we sit down with chefs, food lovers, and hospitality professionals we admire to talk about food and the culinary world. Through their personal memories, unique perspectives, and the experiences that have shaped their approach to gastronomy, these interviews offer a glimpse into the minds of those shaping the way we eat.

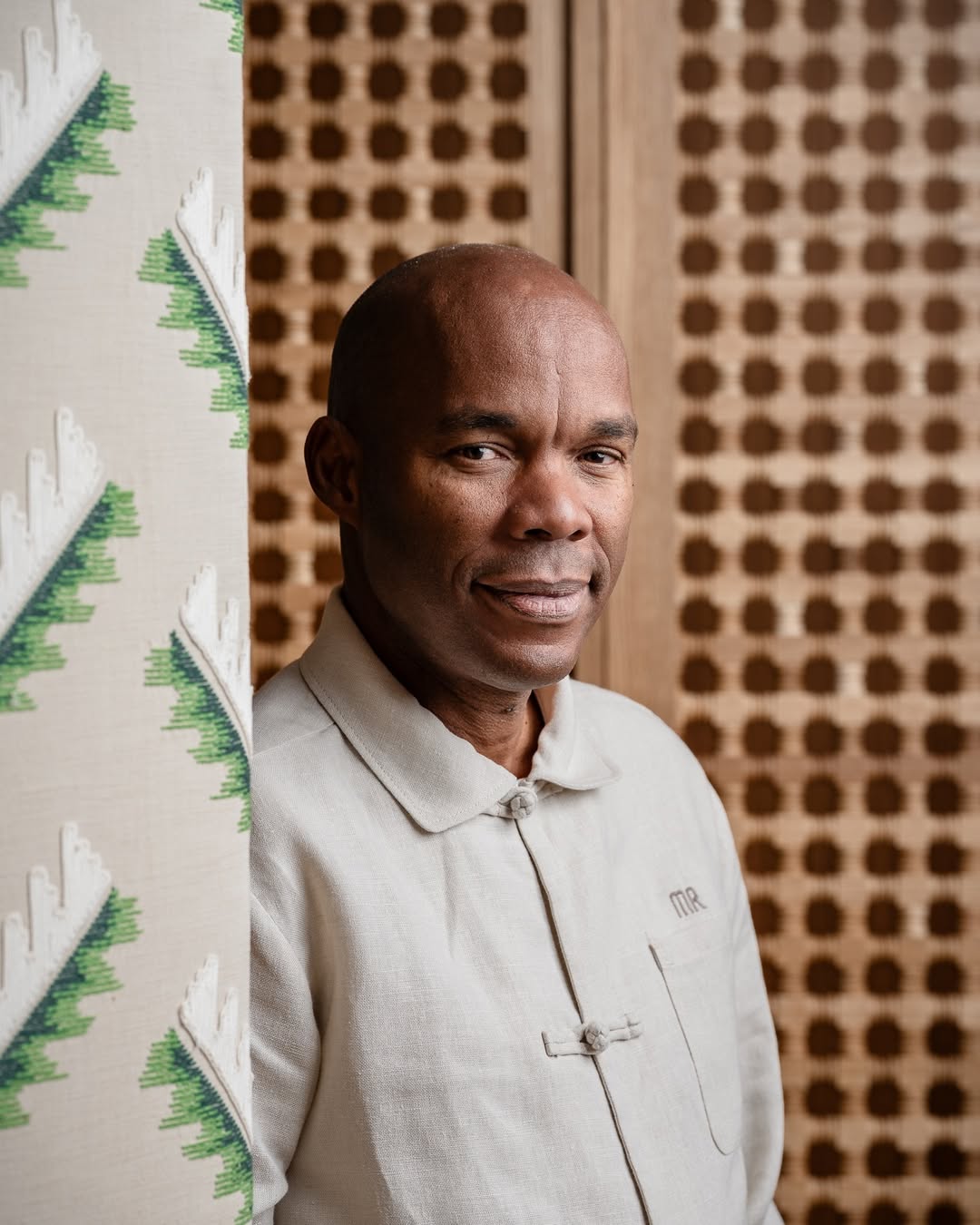

To start with a bang, we talked to Marcel Ravin, two Michelin-starred chef of Blue Bay Marcel Ravin** in Monaco.

I very much admire Chef Marcel Ravin for his culinary philosophy, his dedication to sustainable gastronomy, and the way he seamlessly blends Caribbean and Mediterranean flavors. I had the chance to meet him in Monaco. We had a fascinating conversation, and I was lucky enough to experience his cuisine at lunch.

Born in Martinique, he trained in France before becoming Executive Chef at Monaco’s Blue Bay in 2005. Under his leadership, the restaurant earned two Michelin stars. His cuisine, infused with the bold spices and ingredients of his Caribbean roots, tells a story of heritage and innovation. What I admire most is his commitment to sustainability—sourcing from his organic garden and local producer —proving that exceptional cuisine can also be responsible and thoughtful.